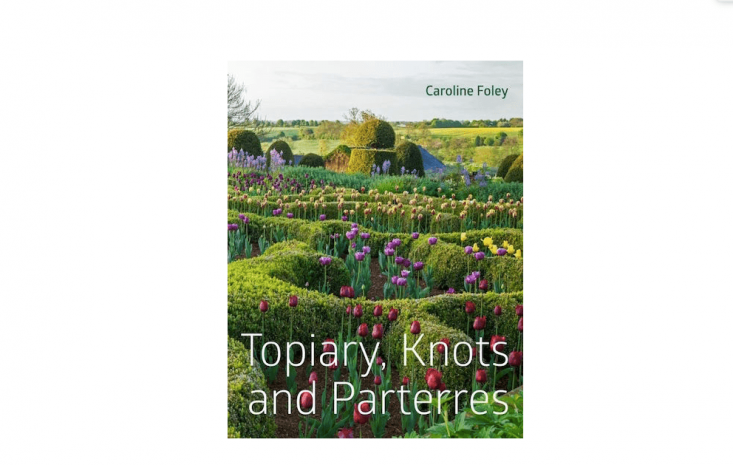

Since its inception a couple of years ago, Pimpernel Press has carved a niche as the garden library-building publisher. Classics—not forgotten but in need of a re-boot—have been reissued, along with more récherché flights of fancy. An essential addition is Topiary, Knots and Parterres, published today. Yes, it’s about clipping greenery, but it’s also a universal subject, covering the full gamut, as the author Caroline Foley points out, “from the ridiculous to the sublime.”

Photography by Andrew Lawson, except where noted.

At Broughton Grange, shown here, Tom Stuart-Smith references Italian gardens with exclamation points of cypress, as well as English Arts & Crafts style. The effect is an informal formality, a structure for riotous perennial planting, and a link between the rigidity of the hard landscaping and the flowing shapes of outlying countryside.

Like the words “parterre” and “cloud pruned,” topiary itself can seem mysterious, part of an out-of-reach style that other people do, in Europe or Japan. In fact, cutting into an overgrown boxwood hedge is topiary, and if it is allowed to express itself with natural lumps and bumps, then it is cloud pruned. Parterre simply means “on the ground” though a parterre in this context is a pattern of low hedging. You don’t really need to know what you are doing: evergreens are very forgiving.

Topiary is closely associated with revivals, for instance the first great one, the Renaissance, or the medieval revival of which we still haven’t tired: Arts and Crafts. Owlpen Manor, shown here, was an aesthete’s dream at the beginning of the 20th century, being a deserted Tudor mansion that was then revived and loaded with extra atmosphere. The poet Swinburne described it as “the very finest & highest yew parlour in all England.” Foley guides us through a potentially complex subject at a fair clip, aided by wonderful illustrations.

Landforms: sculpting with turf is not so far off from moulding shapes out of trees and shrubs. In this garden, designed by Wirtz International, grass, trees and paths are the only essentials: the fascination of shape and texture precludes flowers.

In the story of topiary, one particular thread seems most relevant to today’s gardeners: how to combine naturalistic planting with a strong garden structure. In the beginning, Victorian plantsman and author of The Wild Garden William Robinson pronounced that clipping of any kind was an abomination. The timeline takes in the innovations of Karl Foerster in Germany, whose interest was in hardy plants with structural grasses (he gave us the great grass Calamagrostis acutifolia ‘Karl Foerster’). Foerster in turn influenced Mien Ruys in Holland, who combined the naturalistic with the formal, and their successor is Piet Oudolf. The book puts all of this into perspective.

Walls of yew have the potential of architecture, while shapes of yew bring humor or elegance, and vitally: something to look at in winter.

N.B.: Inspired to try your hand at clipping? See:

- Topiary with a Softer Side.

- Topiary: Cloud Pruning as an Arboreal Art.

- 10 Garden Ideas to Steal from Sissinghurst Castle.

Have a Question or Comment About This Post?

Join the conversation