Cornelian cherries ripen in late summer on dogwood trees. And that’s not a typo. While the glossy fruits scarlet fruits ripening in late summer do resemble cherries (in an oblong way) they belong to the Cornus, or dogwood, genus. In North America Cornus mas and C. officinalis are two very similar-looking introduced dogwoods whose roots are in Europe and Asia. In the regions where they grow, spanning cultures and cuisines, the fruits are a seasonal highlight, and in some countries, like Turkey, they are an important commercial crop. Stateside, cornelian cherries are not much understood, as a food. Instead, the hardy trees are planted for the effusive yellow blossoms that appear in late winter or very early spring, a bright sign of life against a barren, cold landscape.

Cornelian cherry olives are just one reason to plant this hardy tree.

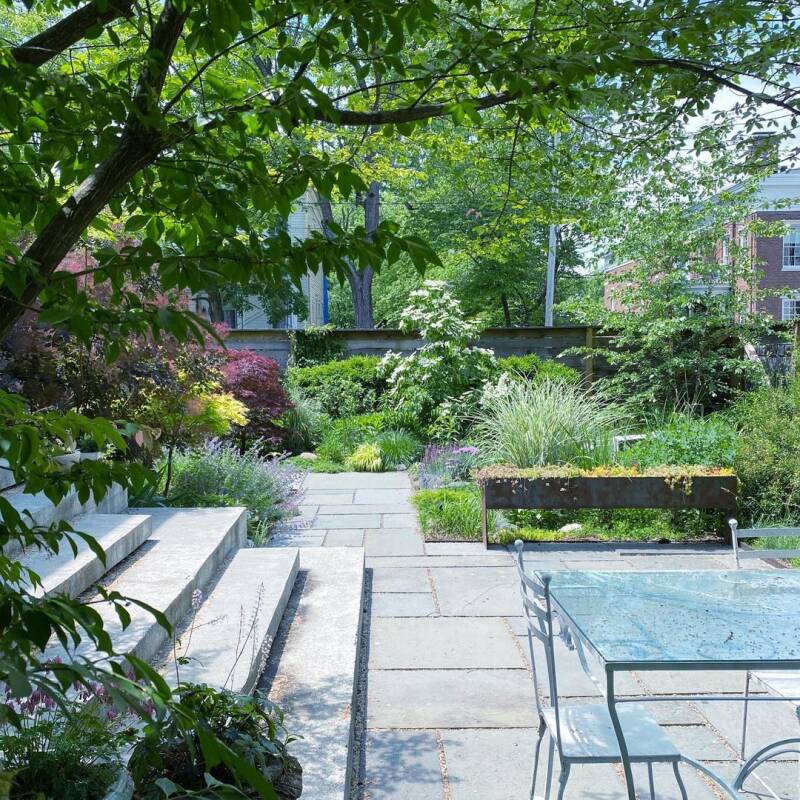

Photography by Marie Viljoen.

Cornelian cherries think about breaking bud in late winter, keeping company with Asian witch hazel and winter honeysuckle, hellebores, and winter aconite. They are cold-hardy, and can be grown from USDA zones 4 – 8. Full sun is best for optimal fruit production. The trees are self fertile but benefit from cross-pollination with another tree.

That first glimpse of yellow is an optimistic moment, signaling that spring is around the corner, even if another month of freezes follows.

In terms of food, in the broad arc of their various native regions in the Eastern Mediterranean and Eastern Europe, the Middle East and East Asia, the tart, Vitamin C-rich fruit of cornelian cherries (also called cornels), is valued and used to make juice, preserves and jams, Cornelian cherry olives, liqueurs, and sauces—or eaten fresh, or dried. The fruit is even mentioned in Homer’s Odyssey in a curious scene where his men, apparently intensely offensive to Circe and transformed by her into pigs, are penned, “weeping”, into a sty where they are fed “forest nuts, acorns, and cornel-berries—the usual food of pigs that wallow in the mud.” Lucky pigs. Maybe the snacks cheered them up and dried their tears until she reversed her magic.

On trees in the Northeast, hard green fruits form by July. On their journey to ripeness they turn pale, then pink, scarlet, deep red, and finally, maroon, when they are at their softest and most plum-like.

Every degree of cornelian cherry ripeness has a use. When green they yield a tart syrup if combined with sugar and allowed to ferment for weeks. The pale to pink stage is ideal for cornelian cherry olives. The process is easy, and the result gratifyingly delicious.

Annually, I use cornelian cherries to make a savory, sweet-and-sour condiment inspired by Georgian tkemali (sour plum) sauce. My version is very simple: the fruits’ cooked pulp flavored with coriander seeds, salt, and sugar. The mixture is cooked gently before being bottled and kept in the fridge.

Cooking cornelian cherries with a little water and then food-milling them is a simple way to extract a tart and versatile juice (to use like lemon juice). The seedless purée can be turned into fruit butters or sauces.

Cooking the whole, ripe fruit gently with sugar and allowing the mixture boil, then cool completely before boiling again, yields succulent preserved cornels, still brilliantly red, with a tart heart wrapped in glacé-like sweetness. They are literally mouthwatering. I like to nibble them whole, or use them pitted as toppings for cookies, or savory canapés.

Pickled Cornelian Cherry Olives

Succulent and salty-sour, these are delightful snacks. The brine I use for making cornelian cherry olives is strong: about 15 percent strength, in terms of the salt to water ratio by weight. To make a larger quantity of cornelian cherry olives, just make sure that the salt-water ratio stays the same (it’s 2 tablespoons salt to every cup of water). Make enough brine to cover the fruit. I like to use sea salt.

For the seasoning stage substitute your favorite herbs and citrus.

Brining

- 2 cups (16 oz) water

- 4 Tablespoons (about 1.4 oz) table salt

- 1 cup (about 5 oz) unripe cornelian cherries, pale to pink in color

Seasoning

- 1 strip Meyer lemon or orange zest

- 4 small branches thyme

- 3 small branches winter savory

- Extra virgin olive oil to cover

Combine the water and salt in a jug or bowl and stir to dissolve. Pack the cornels in a large jar (they should fill the jar only about halfway) and pour over the brine. Cover and leave out at room temperature, out of direct sunlight, for four weeks. If you check on them you’ll notice that the fruit will float for several days before sinking. After four weeks remove the cornels, rinse and dry them, and transfer to a smaller jar with the zest, herbs, and olive oil, and add the lid. Leave out for 12 hours, and then transfer to the fridge. They’ll taste good right away but give them a week to develop more flavor.

For more recipes using fruit, see:

- Taste of Summer: Surprising and Savory Ways to Enjoy Stone Fruit

- Pawpaw: A Native Fruit that Tastes Like the Tropics

- Beach Plum: A Resilient Native Shrub for Flowers, Fruit, and Gin

Have a Question or Comment About This Post?

Join the conversation