Just as pets resemble their owners, the 5.2 million trees that manage to survive in Manhattan and its boroughs closely echo the mad mix of humanity that calls the metropolis home. Some are young and struggling, some tall and far reaching, quite a few are drop-dead gorgeous, many have been around seemingly forever, most are anonymous. And all have stories to tell. Have you been listening?

Fortunately, writer, photographer, and former parks employee Benjamin Swett has. For his book, New York City of Trees, Swett roamed the city, from the Bronx to Washington Square Park to Staten Island, and from garden to sidewalk to highway median, photographing and chronicling the stories behind some of New York’s wildest and most stalwart residents.

Photographs by Benjamin Swett.

Above: This tulip tree, the tallest tree in Queens, overlooks six lanes of traffic on the Long Island Expressway. After comparing the tree’s measurements with those from a 1943 park map, Swett discussed its “balding bark and narrow, dense crown” with a specialist at Columbia University’s Tree Ring Lab and surmises it could be 168 years old.

Above: Swett wasn’t fixed on merely finding out the age of the 50 or so trees he investigated; he wanted to celebrate their connection to New York history and the impact trees have on those who live in their midst.

“We know that trees improve living conditions in cities by filtering and cooling the air, absorbing excess rainwater, and making neighborhoods more attractive,” he writes. “But little has been said about the importance of trees as keepers of a city’s past. The aim in taking these pictures–aside from taking the best photographs I could–was to try to bring back into focus an aspect of the city that most people tend to take for granted until something happens to it. The idea has been to remind New Yorkers how much of their own lives and the lives of neighbors these trees quietly contain.”

He photographed this Yoshino cherry, one of 27 specimens that form a double row along the east side of the Central Park Reservoir, early in the morning “before the sun had a chance to introduce its fatal yellows.” It arrived in 1912, he tells us, as part of a gift of 2,000 cherry trees to the city from the city of Tokyo, and was a replacement for an earlier shipment, to celebrate the 300th anniversary of Henry Hudson’s exploration of the Hudson, that was entirely lost at sea.

Above: “As everyone knows, the tree of heaven is a weed tree, a vicious invasive that would take root in a soda can if given the opportunity,” writes Swett. “Just the sight of it, in many people’s minds, breeds thoughts of insurrection against the urban grid.”

Ailanthus, as its properly known, was introduced, he notes, as an ornamental from China in 1784 and is now the most common tree in New York. The specimens shown here sprouted in “classic ailanthus territory,” in a forgotten spot under an abandoned railroad track. Eight months later, Swett returned and found them missing. Just weeks before the photo was taken, he later learned, the city council had voted to turn the defunct railroad track into a park. It’s now part of the thriving and much-copied High Line, which features sophisticated plantings that evoke the look of the tracks when they were long abandoned.

Above: A flourishing Chinese Maidenhair ginkgo overlooks Broadway along the southeast corner of Isham Park, in Inwood. First imported from China as specimen trees for parks and estates, the species, Swett explains, exhibited great hardiness, and soon became a favorite for not-very-hospitable city streets. “Building superintendents love them,” he notes, “because in the fall their leaves drop all at once, making cleanup easier.”

Swett traces this one’s origins to the late 1860s or 1870s when it was likely planted at the entrance of tanner William B. Isham’s estate, now an urban park with nothing like an estate in the vicinity. It stands on what was the Boston Post Road, the main route to and from Manhattan. If you visit, look for the 18th century marker that Swett says is hidden on the retaining wall beneath it. Part of Ben Franklin’s traffic marker program, it indicates that City Hall is 12 miles away.

Above: Swett captured this English elm in Madison Square Park as it was failing. One of a grove of seven that originally shaded the park, which opened in 1847, it may have been damaged by extensive paving–Swett notes that its roots “at some point curled back around each other and around the trunk in a process known as girdling”–or, he says, it may have succumbed to old age.

Tree fashions, Swett points out, are ever changing. Planted in the Boston Common, the English elm was for a 19th-century moment the specimen of choice for parks, streets, and gardens. The horse chestnut and osage orange later came in vogue, followed by the soon-to-be-diseased American elm, and, in more recent years, the resilient Callery pear, honeylocust, and Norway maple. Proliferation, as it always does, breeds a desire for the new. But the remains of the English elm are still in place. Now just a gray shaft, it was in the prime of its life back in 1931 when the Empire State Building rose in the skyline behind it.

Above: Swett was drawn to this European Hornbeam at the New York Botanical Garden in the Bronx, not because it’s exotic or impressively old or tall, but because it’s so good looking. “Sometimes–and often, as with people simply because of the way they appear on a particular day, in some combination of weather and light–a tree stands out for the perfection of its form…It is simply, purely, what it is supposed to be.”

Above: While passing a parking lot en route to a Chelsea art opening, Swett discovered one of his favorite trees, a humble Callery pear. He visited it often, in different seasons.

Above: Callery pear trees, Swett says, are prized for their fast growth, tolerance to pollution, and beauty in all seasons. “It was not a big or unusual or important tree,” he writes, “but it had a nice shape and went well with the building behind it and I liked it.”

Above: In the most poignant portrait in his book, Swett captured the crane that he discovered in place of his tree–removed out of the blue to make way for an extension of the No. 7 subway line. “Maybe,” he wonders, “somebody thought that so many Callery pears are planted in Manhattan (about 7,800 at last count) nobody would mind the loss of this one.”

Above: A century-old copper beach with an auburn afro-like canopy stands at the top of the lawn at Wave Hill, a tiny gem of a public garden in the Bronx where in fall and spring Swett teaches a series of tree photography classes. For more on Wave Hill, see A Visit to an Amazing Fall Garden.

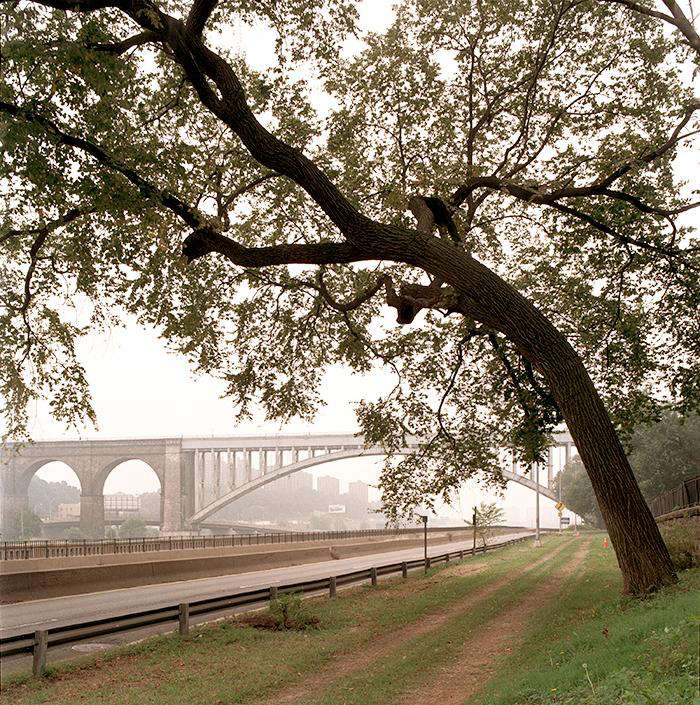

Above: Like most successful New Yorkers, the American elm has the ability to bend and stretch rather than be crowded out. This one, likely planted in 1934 by Robert Moses’ crew, grows on the side of Harlem River Drive originally known as the Speedway. The bridge behind it, the High Bridge, dates to 1848 and once carried water from the Croton Aqueduct across the Harlem River. Intended as a pedestrian-only walkway–Edgar Allan Poe “spent much of the last melancholy year of his life strolling across it from his cottage on Kingsbridge Road,” writes Swett–it’s slated to reopen to walkers some time next year.

Above: New York City of Treesis available for $11.01 from Amazon. Trees of New York City, a new edition of the book, came out in 2017 from Countryman Press.

The book’s original cover (above) shows a century-old cluster of Katsura trees in a park in Flushing, Queens. Its fallen leaves, according to Swett, smell like cotton candy and its branches create a cathedral-like canopy, making the clearing under them a favorite spot for wedding photos. Swett traces the trees’ origin to seeds sent home from Japan by one of President Lincoln’s consuls whose brother ran a nursery in Queens.

As part of the Parks Department’s program to preserve the genetic stock of the city’s designated Great Trees, these Katsuras, he reassures us, have been cloned and eventually will be planted in all five boroughs. In other words, New York’s tree future seems promising. Here’s hoping that tomorrow’s sprouts make their way into books like this one.

Do you want to grow your own giant tree? See “A (Tiny) Giant Sequoia Tree.”

N.B.: This is an update of a post published May 13, 2013.

Have a Question or Comment About This Post?

Join the conversation